On 20 July 1969, lunar landing module Eagle opened up onto the surface of the Moon. A few years later, on 15 September 1976, a different, rather larger module opened up on Manchester's St Ann's Square. The latter represented not quite so giant a leap, perhaps, but it was certainly a huge achievement and it's come to have its own special cultural significance.

Needless to say, the Royal Exchange Theatre Company takes its name from the building that houses it. The present Exchange building isn’t the first, though. In fact, it’s the third. The original was built in 1729 in what was then known as ‘Market Place’, roughly the site of Manchester’s large Marks & Spencer store. At that time St Ann’s Square, round the corner, had only recently been developed beyond being a cornfield.

The intended purpose of the Exchange was to provide a place for assorted business folk, merchants and manufacturers to meet, talk and strike deals. However, it seems that industry in the town hadn’t necessarily reached the levels that required a dedicated Exchange, and over the years parts of the building started to be used for different purposes. Indeed, the oldest existing records suggest that the first public staging of a play in Manchester, namely a performance of Farquhar’s comedy THE RECRUITING OFFICER, took place on the site in 1748. Over time, the Exchange fell into a state of disrepair and some disrepute before being demolished in 1792. Ironically. It was around this time that Manchester’s involvement in the cotton trade really began to gather momentum and the need for a dedicated business meeting place made itself clear. So it was that a second Exchange was built, opening in 1809. Situated on the current site (or at least part of it), the new building was a hugely lavish, finely-appointed affair, funded by subscription and accessible only to members, complete with a well-stocked newsroom, a bar and a dining hall which could house an orchestra and double as a ballroom. Overall, this was a grand space fit to act as the hub of the textile trade for the movers and shakers of ‘Cottonopolis’.

It must be acknowledged though that, by the very nature of the 19th Century cotton trade, Manchester was also implicated in the slave trade. Along different parts of one route, ships that carried raw cotton as saleable cargo would also transport humans, for the same reason. The links from this to those who walked the floor of the Exchange weren’t often direct, but there were certainly local industrialists involved in the slave trade, however obliquely or covertly. Bankers and insurers, for instance, may well have been responsible for underwriting slave ships, and there are scattered examples of wealthy business families who actively embraced, and indeed enthusiastically supported, the slave trade.

The working people of Manchester tended to have their own feelings on these matters. Famously, the city was instrumental in the 1807 Act of Parliament that abolished the trading of enslaved people and it’s said that one in five Mancunians had signed a petition for abolition. Nevertheless, for a time loopholes were found to circumvent the Act, and as trade boomed, Lancashire textile workers were largely processing cotton picked in the American South by enslaved people from Africa or the West Indies. It’s an uncomfortable truth, but to a degree the riches that poured into Manchester were tainted. For all that, though, cotton was far from the only business trade to be conducted at the Exchange. Indeed, the first Exchange had been built before the cotton trade had been fully established, and ultimately the building would outlast it.

Nor was the Exchange of old free of unrest. In April 1812, with the actions of the Luddite movement approaching their peak and the tragedy of Peterloo on the near horizon, a meeting was scheduled in the upper room of the building to draft a congratulatory letter to the Prince Regent. The subject was his support for Spencer Perceval’s Tory government, public contempt for which was so strong that, when news of the meeting spread, it was swiftly cancelled, only for an angry mob to break into the Exchange and wreck the newsroom before being dispelled by the military. (Much later, this scene was played out as part of the theatre’s 2019 staging of THERE IS A LIGHT THAT NEVER GOES OUT, co-produced with Kandinsky.)

Nevertheless, as a whole the Exchange was thriving and membership was escalating swiftly, as a result of which the existing building was extended to twice its size in 1849. When Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and assorted other members of the Royal Family made an official visit to Manchester in October 1850, the expanded Exchange building was deemed suitable to host the large-scale civil reception. The following month, official word arrived that Victoria had given the building her seal of approval, from which point it became known as the Royal Exchange. (This even predated Manchester receiving official city status, which didn’t happen until April 1853.)

As Manchester continued to flourish at the pinnacle of the Industrial Revolution, it was decided to expand the Exchange building yet again. Though various possibilities were mooted, including relocation, eventually the existing building was pulled down and another, larger Royal Exchange built on the same site. Completed and opened in 1874, the new Exchange’s Great Hall was 206ft by 96ft, with a glass dome 120ft above its centre. It was ten times the size of the original Exchange built on the same site, and indeed the Great Hall was often referred to as ‘the biggest room in the world’. This seems to have been more of an honorary title than an empirical fact, though it could lay claim to being the largest commercial room in existence.

The biggest room in the world

Essentially this was the same building that’s still standing today, aside from two significant developments. Firstly, the Exchange underwent yet another extension to meet demand, completed in 1921 and officially opened by King George V. (It might be noted that George IV had been the troublesome Prince Regent who’d caused a riot in the Exchange over a century earlier). Secondly, on 22 December 1940 it was hit by a bomb during an air raid as part of the ‘Manchester Blitz’, destroying half of the building. As such, the size of the Exchange still fluctuated over the years.

Towards the end of the 1960s, the Exchange as it stood ceased to have much purpose. Modern technological developments had transformed how industry deals were conducted. Shops and offices had sprung up in the areas around the building but precious little actual trading was being conducted with membership falling to an all-time low. The building was duly sold off, and the final day of trading was 31 December 1968.

By that point, though, the cast of characters who would lead the building onto its next stage had already begun to assemble.

After the Blitz

In the years before the Royal Exchange Theatre opened its doors, the main players met and worked together in various combinations. The very earliest starting point for their story would be the post-war theatre school run by the Old Vic in London. Headed up by the pioneering French theatre-maker Michel Saint-Denis, who’d run the London Theatre School before the war, from 1945 the Old Vic Theatre School was based in what remained of the bombed-out theatre itself, before relocating to a former high school building in Dulwich. Around a hundred students between the ages of 18 and 21 were given a rigorous, intensive training in the arts, with the full-time course covering all aspects of theatre-making. Saint-Denis was a keen advocate of organic, multi-disciplinary training, and though the school didn’t last long – it was dissolved in 1952 in a budget-saving move – it casts a long shadow. A cohort of young, eager graduates, like-minded souls with ambitions to shake off the play-it-safe fustiness of post-war British theatre, was despatched out into the industry.

The first fruits of this came in March 1954 when a modest theatre company was established by two of the school’s graduates: Richard Negri, who had recently inherited some money from his late father, and his friend and associate Frank Dunlop. Neither man was Mancunian, but on investigation it was discovered that a suitable space for their enterprise existed in a public hall above a Conservative Club in the south Manchester suburb of Chorlton-cum-Hardy. It had previously been used as a theatre and had only recently been vacated by Chorlton Repertory Theatre Club. Negri, in his capacity as designer, elected to take steps to mask some of the less appealing aspects of the space, constructing a ‘tent’ made of shrouding material painted with stripes, within the hall, informing the local press, “we want to make the audience feel that they are part of the play”.

The newly-named Piccolo Theatre Company duly set about putting on bold productions of lesser-seen plays, taking in the Quintero brothers’ THE WOMEN HAVE THEIR WAY, Kesselring’s ARSENIC AND OLD LACE and the true-life Victoria melodrama MARIA MARTEN. This was hugely ambitious work for a small provincial theatre, and Dunlop and Negri were assisted in their endeavours by various other graduates of the Old Vic Theatre School who they’d invited along to get involved. As a result, the Piccolo Players included many of their fellow former students, including James Maxwell, Rosalind Knight, Patrick Wymark, Avril Elgar, Dilys Hamlett, Eric Thompson and Lee Montague. (Future national treasure Bernard Cribbins acted as one of the company’s stage managers.) The Piccolo’s particular set-up proved problematic. Legally, the venue was required to operate as a members-only club, but cheerfully welcomed customers without asking them to become members, which resulted in a police investigation and a swiftly dismissed court hearing.

In critical terms, the Piccolo Theatre Company punched way above its weight and caused quite a stir, but in practice it lasted less than a year. The pressure of operating on a shoestring became too great, and Negri is reported to have considered abandoning theatre to become a monk. Again, its real impact was felt further down the line. Dunlop went on to enjoy a stellar career in theatre, establishing the New Vic in 1970, and became the director of Edinburgh International Festival from 1984-91. Negri, too, had a bright future ahead of him.

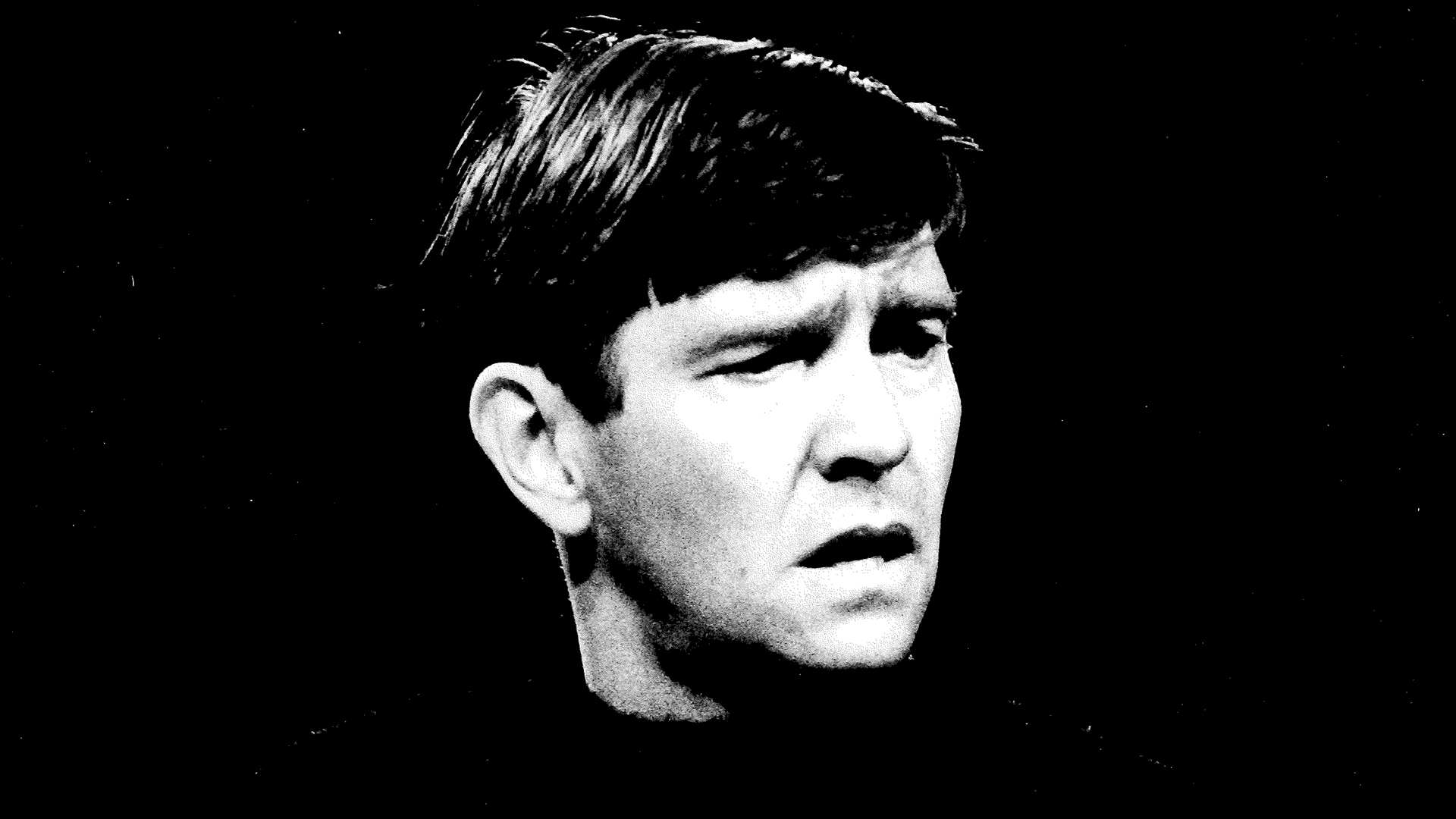

As the Old Vic theatre school graduates found work around the country, they continued to share ambitions of establishing a permanent venue in which to stage fresh, challenging work.. They stayed in touch, often making a point of bringing each other in to work on projects. Along the way, they also met other like-minded souls who became part of the ‘group’. Casper Wrede, another attendee of the Old Vic school, came from Finnish nobility and had been involved in the Piccolo Theatre. During the early 50s, he’d been directing productions for Oxford University Drama Society. After one performance, Wrede was approached by an appreciative undergraduate who was keen to work in theatre. The student in question was Michael Elliott, who would swiftly become a close associate of Wrede’s. In 1959, Wrede established the 59 Theatre Company, based at the Lyric Opera House in Hammersmith, with the intention of challenging the orthodoxy of British theatre programming. As the name suggested, it sought to present theatre tailored for its time. The privately-funded company only lasted eight months and proved to be something of a financial disaster, but in that time it succeeded in staging pioneering productions of the likes of BRAND and LITTLE EYOLF by Ibsen, plus Alun Owen’s ROUGH AND READY LOT and Georg Büchner’s DANTON’S DEATH. Some were directed by Wrede, others by Michael Elliott, installed as the company’s assistant Artistic Director. In fact, Elliott’s production of BRAND was his first professional solo stage directing credit. Meanwhile, a new collaborator, Richard Pilbrow, became the company’s lighting designer.

Other Old Vic Theatre School alumni were involved, though: Richard Negri was brought into the company as designer, while DANTON’S DEATH starred Patrick Wymark and had been adapted from the German original by James Maxwell. The group of friends and collaborators was becoming increasingly tight-knit. Massachusetts-born Maxwell had married fellow Old Vic school graduate Avril Elgar in 1952. Wrede had married another fellow graduate, Dilys Hamlett, in 1951, and Rosalind Knight, who had met Elliott socially through the group, married him just after the end of the 59 Theatre Company’s brief lifespan.

The parties in question continued to coalesce and collaborate during the 1960s. For instance, when Michael Elliott was made Artistic Director of the Old Vic in 1962, he brought in Wrede to share directing duties on a season of plays, before the National Theatre took the building over the following year.

When the final key member of this ambitious group, by some distance the youngest, fell into place, it happened in Manchester. Braham Murray was a young director from North London, and his theatrical education involved staging ambitious student productions in Oxford while studying for an English degree he never completed. In 1965, within a year of leaving Oxford, Murray was appointed Artistic Director of Manchester’s Century Theatre, aka ‘the Blue Box’ – a resourceful set-up involving three blue ex-military pantechnicon lorries that interlocked to create a 225-seater auditorium, each one pulling trailers containing kit to assemble into temporary accommodation for the company and a box office. In this way, the company had been touring shows around the North since the Fifties, but now it was stationed at Manchester’s University Theatre building on Oxford Rd (which later became part of Contact).

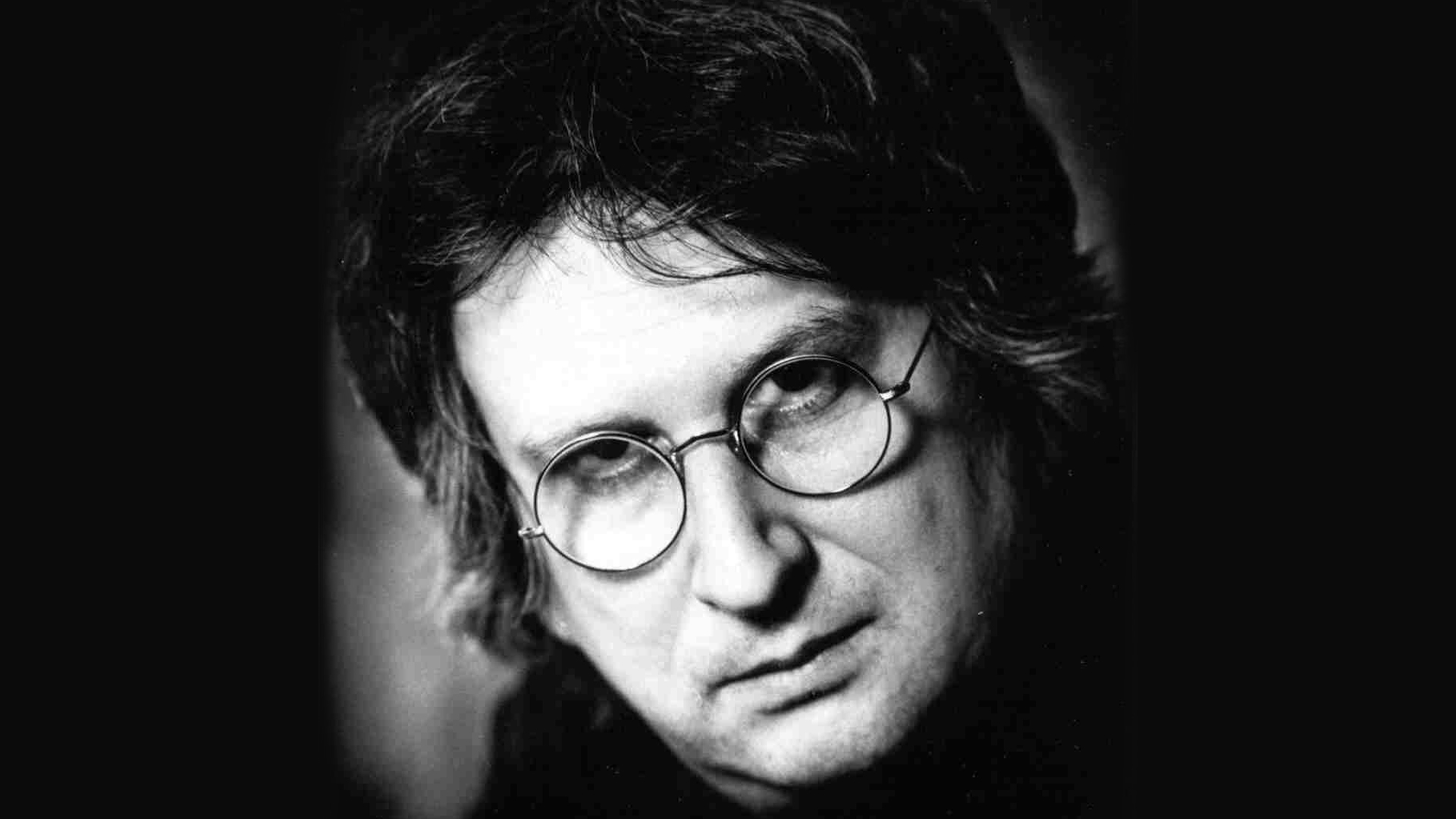

Murray was an admirer of Wrede and Elliott’s work – in his youth he’d seen, and been hugely inspired by, the 59 Theatre production of BRAND – and brought them both in to direct shows for the Century Theatre. Like them, though, he was eager to do something on a larger, more permanent scale. When Century Theatre parted ways with the University Theatre in 1968 (ultimately taking up residence in Keswick), Murray, Elliott and Wrede, along with their friend and associate Richard Pilbrow, founded 69 Theatre Company, the very name a clear nod to the work and legacy of 59 Theatre Company.

Initially, the company was based at the recently-opened 295-seater University Theatre, which had been designed with input from the late director Stephen Joseph. Joseph had been a pioneering proponent of ‘theatre in the round’, and though the University Theatre itself wasn’t technically in the round, the stage layout was particularly flexible.

The arrangement wasn’t permanent, though, and in time the company began to seek funding, and a potential location, for their own venue, initially hoping to build one from scratch. In and of itself this was a hugely ambitious plan. By the mid 1970s, a great number of long-established Manchester theatres had closed their doors. Only a handful remained, of which two – the Palace and the Opera House – were also under serious threat of closure.

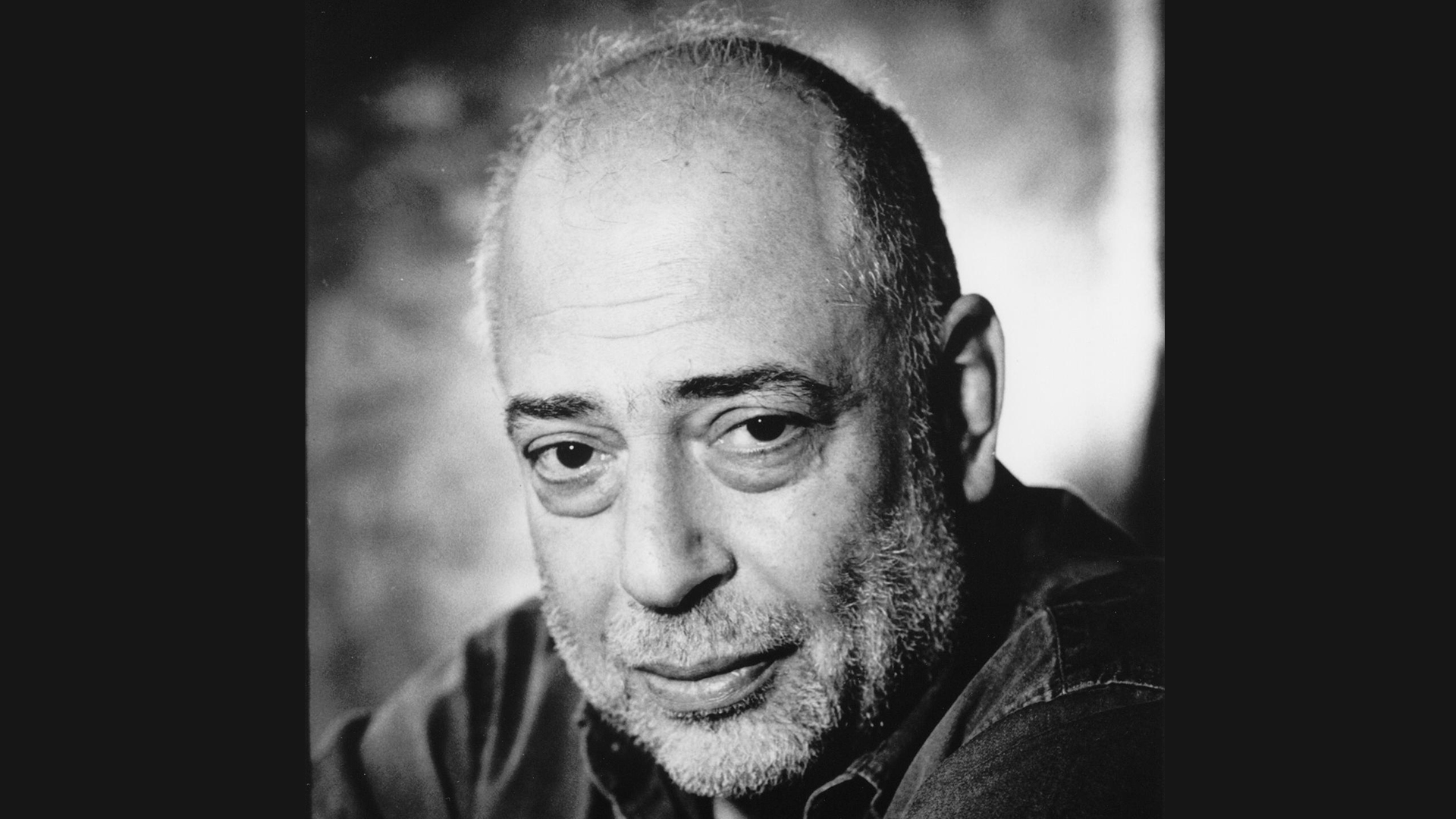

Pilbrow soon exited the 69 Theatre Company to focus on his flourishing career in lighting design, but new recruits were forthcoming. James Maxwell and Richard Negri were already in the orbit of the group, working on new productions with long-time friends and colleagues. Maxwell became an artistic director in 1973; in 1974, so did Negri.

Behind the scenes, certain key figures were moving the company’s plans forward. As Administrator, Bob Scott co-ordinated the raising of finances for a venue. As leader of the company’s unofficial advisory ‘council’, local stockbroker Peter Henriques used his considerable influence to explore business possibilities. It was Henriques who suggested to the 69 Theatre directorship that they might consider, even as only a temporary solution, the Royal Exchange building – which, in a neat coincidence, had become vacant and available as of the first day of 1969. It proved to be a popular idea. On an initial site visit in 1971, Richard Negri was struck by the notion of constructing a layered interior theatre space that would resemble a rose.

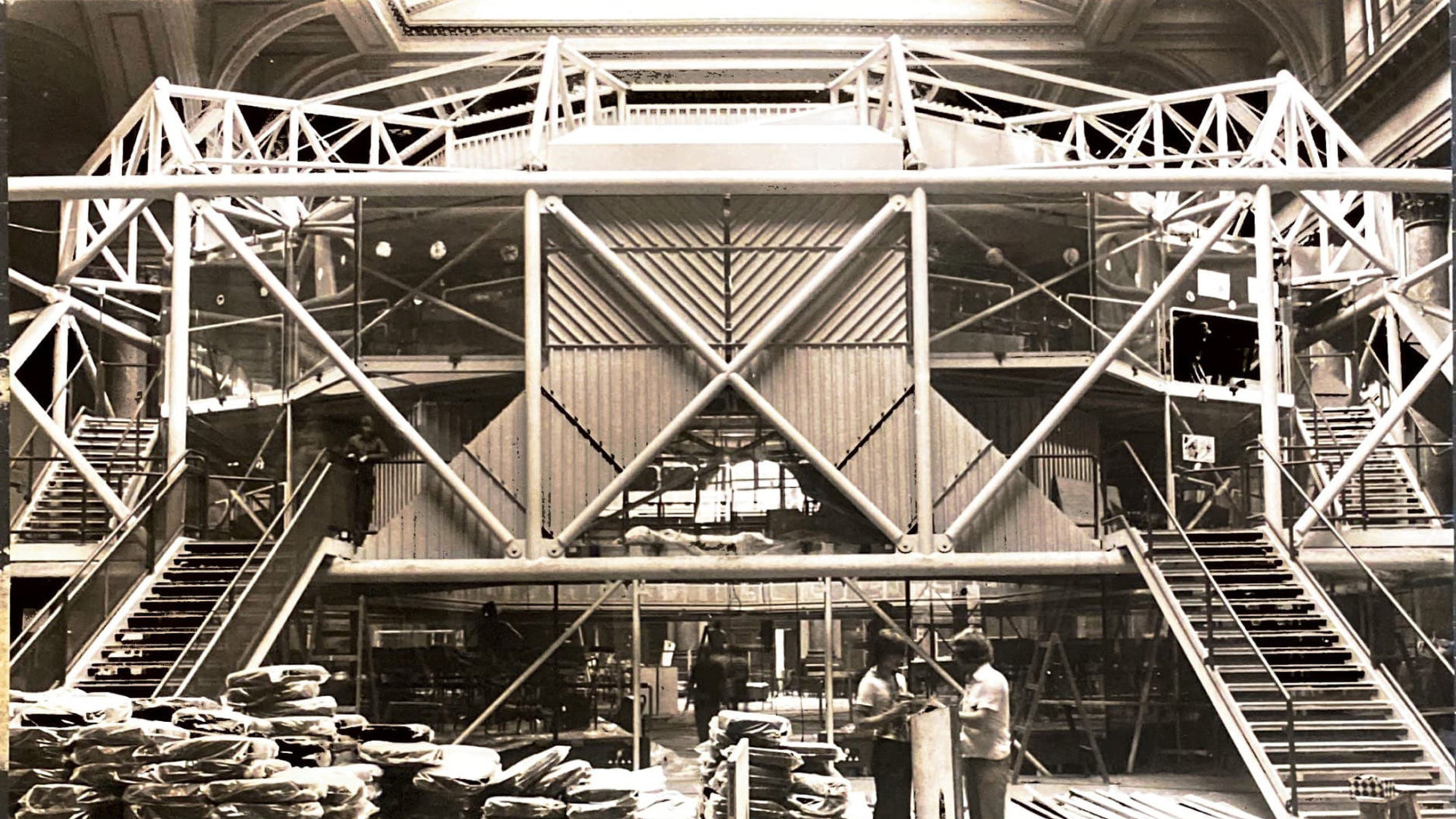

While working towards that end, unexpected possibilities presented themselves. Greater Manchester was due to be incorporated as a county in 1974, and in the run-up, the city council was keen to mark the occasion with a special festival. For the occasion, the 69 Theatre Company was asked to create a temporary performance space within the Exchange’s Great Hall. Designed by Laurie Dennett, it recycled materials from other sites, including scaffolding, seating and boarding – but the exterior was draped in fabric, which led to it being nicknamed ‘The Tent’. Intended to fulfil its purpose for only three weeks from May 1973 for a production of Shaw’s ARMS AND THE MAN, it proved to be a resounding success and for a time it was considered as a permanent option. Insurers demurred, however, and The Tent was eventually dismantled in February 1974. As an experiment, though, it had proved to be a very instructive experience.

The Tent

The project gathered momentum as further finances were raised via fundraising events and gala performances. Substantial grants were forthcoming from the Arts Council and Manchester City Council, alongside donations from local businesses such as Granada and private individuals, including many prominent actors. Gradually, everything fell into place. For just over a year from late 1974, the 69 Theatre Company staged productions in the nave of Manchester Cathedral. On 14 April 1975, work on the Royal Exchange Theatre began, and by early 1976, the 69 Theatre Company was officially renamed the Royal Exchange Theatre Company.

As designer, Richard Negri envisioned a seven-sided theatre constructed from tubular steel. The end result is often tagged ‘in the round’, but Negri wasn’t fond of the term. Essentially, he hoped for a space in which the audience, at least on the ground floor, was at the same level as the performers – indeed, even on upper levels, no-one would be more than ten metres away from the stage. For Negri, the audience members should be something like the Forest of Arden, surrounding the stage. To this end, he had the seats died a very particular shade of ‘forest green’. There were hitches along the way, though. The tubular steel Negri required proved to be in short supply as it was also used in the construction on North Sea oil rigs. A significant delay looked likely before Harold ‘Monty’ Finniston, Chairman of British Steel, intervened directly. More pressingly, it was discovered that the floor of the Exchange wouldn’t take the total weight of the occupied theatre, but the ingenious solution was to suspend the upper floors from the existing pillars supporting the building’s central dome. Even this caused issues, though. Negri wanted the construct to be seven-sided, but it was thought to be impossible to suspend the structure unless it was eight-sided. There were tense moments before an elderly building worker piped up with a method of achieving it and maintaining the required heptagonal shape.

The finished theatre, ready to seat a maximum audience of 700, was officially opened by Laurence Olivier on Wednesday 15 September 1976 launching with a production of Sheridan’s THE RIVALS, directed by Murray. The cast included Tom Courtenay, Patricia Routledge and James Maxwell. The same cast performed in rep with a production of von Kleist’s THE PRINCE OF HOMBURG directed by Wrede, alternating with THE RIVALS every other night. Subsequent early productions at the Exchange involved Rosalind Knight, Avril Elgar, Dilys Hamlett, Eric Thompson and Lee Montague – each of them erstwhile students of the Old Vic Theatre School.

The Theatre

Over the years since, the Royal Exchange has established itself as one of the country’s most significant theatre companies, staging bold, engaging, often challenging work, just as the founding Artistic Directors had intended. Naturally, the directorship has changed down the decades, with each new incumbent bringing their own style to the company’s programme. Gregory Hersov had been associated with the theatre since 1979, and became a long-standing Artistic Director from 1987. Matthew Lloyd joined as an Artistic Director from 1998 to 2001, and Marianne Elliott held the role from 1998 to 2002. A hugely successful director in her own right, Elliott’s father was Exchange co-founder Michael Elliott, who had died in 1984, aged just 52.

Gradually, the company’s five founding Artistic Directors moved on. Richard Negri left in 1986, holding the title of Honorary Artistic Director until his death in 1999. Likewise, Casper Wrede left in 1990, becoming Honorary Artistic Director until he died in 1998. James Maxwell remained active as an Artistic Director up until his death in 1995. The youngest of the original group, Braham Murray stepped down as Artistic Director in 2012, and died in 2018 at the age of 75.

With a history of more than 400 main house productions over almost 50 years, it’s perhaps unfair to highlight specific shows from the Royal Exchange’s lifespan. Audience members will have their own favourites, from Tom Courteney and Freddie Jones in THE DRESSER, Robert Lindsay in HAMLET or Brian Cox as Ahab in MOBY DICK, to Michael Sheen in LOOK BACK IN ANGER or Don Warrington in KING LEAR. They may have particularly vivid memories of seeing a Trevor Peacock musical, a Joe Orton revival or thrilling new work by Brad Fraser. Or perhaps they’re more partial to the dazzling tradition of Royal Exchange Christmas shows, such as Carol Ann Duffy’s RATS’ TAILS, Victoria Wood’s THAT DAY WE SANG, LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS, THE PRODUCERS, or BETTY: A SORT OF MUSICAL

Audience Favourites

Sadly, a 1996 production of Stanley Houghton’s HINDLE WAKES proved to be momentous for reasons no-one could have foreseen. Just over a week into what was intended to be the show’s month-long run, on Saturday 15 June 1996, Manchester city centre was devastated by the detonation of a 1500kg IRA bomb concealed in a lorry parked on Corporation Street, less than fifty metres away from the Exchange. The damage was extensive.

In the immediate aftermath, the Exchange managed to stage a couple of emergency performances of HINDLE WAKES at the BBC building on Oxford Road, before taking up temporary residence in nearby Upper Campfield Market, just off Deansgate. The market hall dated back to 1878, making it almost exactly the same age as the current Royal Exchange building. Here the company managed to resume its planned schedule, spending a memorable twenty-month stint racking up fourteen productions in a warm, welcoming atmosphere.

By sheer chance, when the bombing occurred, the Exchange was in the advanced stages of applying for a National Lottery grant for an extensive refurbishment. It would be eighteen months before the works were completed – in the process adding a small Studio Theatre space – and the building would reopen. Picking up from before the dramatic interruption, the reopening production was HINDLE WAKES.

In 2008, Sarah Frankcom became an Artistic Director of the company, and when Gregory Hersov stepped down in 2014 Frankcom became the first sole Artistic Director in the Royal Exchange’s history. Notably, she forged a fruitful creative partnership with actor / writer Maxine Peake, which resulted in a number of critically acclaimed Exchange productions including HAMLET, THE SKRIKER, HAPPY DAYS and QUEENS OF THE COAL AGE. Similarly, Frankcom’s work with playwright Simon Stephens included debut productions of ON THE SHORE OF THE WIDE WORLD, PUNK ROCK, BLINDSIDED and LIGHT FALLS. With a contemporary and innovative approach to programming, Frankcom championed the importance of representation, ensuring opportunities for everyone to see themselves on-stage and off, making the Royal Exchange a space that reflected the city.

Productions directed by Sarah Frankcom

In July 2019, it was announced that Frankcom was to be succeed as Artistic Director by the pairing of Roy Alexander Weise and Bryony Shanahan. Before their first season at the helm had been completed, though, it was truncated by the COVID pandemic. In March 2020, the production of Winsome Pinnock’s ROCKETS AND BLUE LIGHTS was forced to close after just two performances. Like theatres around the world, the Royal Exchange went dark for over a year. In June 2021, when official guidance finally permitted it – albeit with careful social distancing still in place – the Exchange reopened with BLOODY ELLE, an acclaimed one-woman show written by and starring Lauryn Redding. Gradually, as the months went on and regulations relaxed, productions were able to return to full-scale.

Reopening the Royal Exchange

Beyond the module, even outside the building itself, a whole range of activities is conducted by the Royal Exchange. For nearby schools, there’s a programme of workshops and backstage tours, and there’s the award-winning Young Company for 14-21 year-olds, offering weekly workshops, annual productions and mentoring opportunities in a wide range of aspects of theatre-making. Mirroring that is the Elders Company, which enables older people to meet up and get involved with creativity and theatre. There’s also Local Exchange, an outreach programme for those across the Greater Manchester community with an interest in what goes on behind the scenes, which also boasts its own travelling pop-up performance space known as ‘The Den’.

The Exchange aims to discover and champion new writers, too. It operates the Writers Exchange programme in partnership with WarnerMedia, and since 2005 it’s been home to the bi-annual international Bruntwood Prize for Playwriting, modelled on similar lines to the earlier Mobil Playwriting Competition which ran from 1984-97.

Today, the Royal Exchange remains keenly aware of its own past. The foyer cafe and bar is named THE RIVALS, in honour of the Sheridan comedy that launched the company back in 1976, and it’s adorned with photos and posters from productions gone by. For almost two years, the Great Hall itself has been adorned with an installation by DISRVPT entitled Holding Space, complete with a poem by Contact CEO Keisha Thompson, displayed on huge drapes, tackling often thorny aspects of the building’s long and varied history.

In 2006, an episode of the ghost-hunting TV show MOST HAUNTED was filming around the building, and down the decades there have indeed been rumours of strange spectral occurrences. Ultimately, though, it doesn’t really matter whether you believe in such things or not. The undeniable fact is that a huge number of fascinating people have passed through the Great Hall down the centuries and left an indelible mark, achieving many remarkable things while within its walls. Hopefully, that will continue to be the case for a long while yet.